Season 5, Episode 5: On Finding One's Voice With The CPA's Rebecca Weston

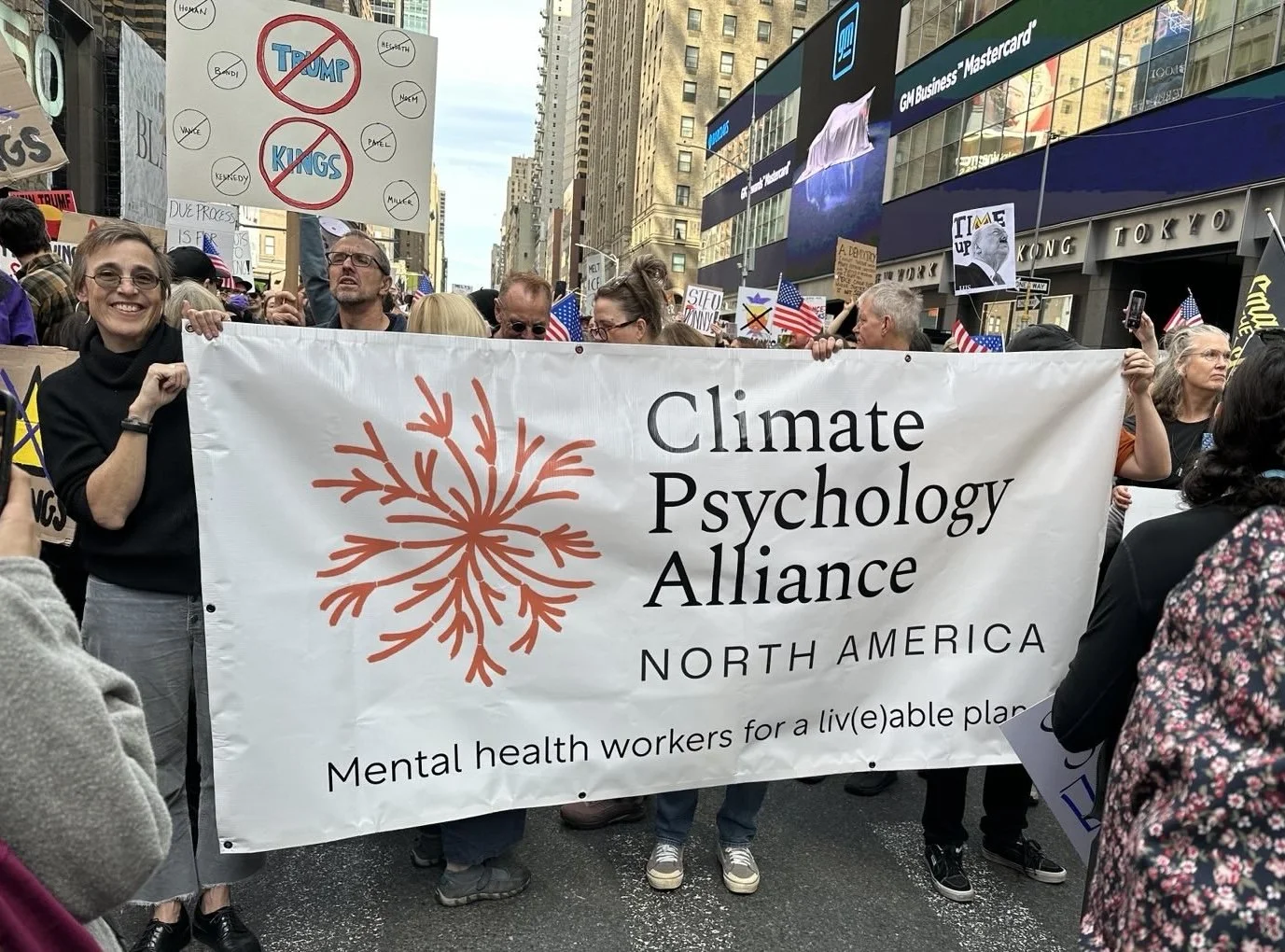

Rebecca Weston at a march on Oct 18, 2025

Thomas and Panu engaged with Rebecca Weston, lawyer, clinician and Co-Executive Director of the Climate Psychology Alliance of North America. Rebecca shared her journey of empowerment about climate therapy, emphasizing the need for empathy and understanding of denial and fear surrounding climate change. The conversation delved into the significance of attachment and relationships in shaping our responses to environmental crises. As an organizational leader, Rebecca reflected on the challenges and growth opportunities within the Climate Psychology Alliance, such as securing funding and support for grassroots climate initiatives.

Links

Transcript

[music: “CC&H theme music”]

Introduction voice: Welcome to Climate Change and Happiness (CC&H), an international podcast that explores the personal side of climate change. Your feelings, what the crisis means to you, and how to cope and thrive. And now, your hosts, Thomas Doherty and Panu Pihkala.

Thomas Doherty: Well hello, I’m Thomas Doherty.

Panu Pihkala: And I am Panu Pihkala.

Doherty: Welcome to Climate Change and Happiness. This is our podcast. This podcast is a show for people around the globe who are thinking and feeling deeply about climate change and other environmental issues. This started as a dialogue between Panu and I that we decided to make public. And, you know, we were a bit of early adopters in this when we were starting to do this work, but now it's much more common to have these conversations. And it's much more common for therapists and other people to be doing public versions of this work. And on that note, we have a really special guest with us.

Rebecca Weston: Hi, my name is Rebecca Weston and I am a private practice clinician full-time and I'm co-executive director of the Climate Psychology Alliance of North America. And I'm really excited and honored to be with you guys.

Doherty: Yes, and so Rebecca knows very well about this idea of public dialogue and she's been helping to steward a huge organization of people that are trying to do climate cafes and put the word out and help the counseling, psychology, therapy field, address all these broad issues of climate and environmental things and all the other associated issues that

are stressing us in the world. And so we're really glad to have Rebecca here to give us a little perspective of her work. Panu, do you want to get us started?

Pihkala: Warmly welcome, Rebecca, also on my behalf. Lovely to be talking directly with you, We have been following each other's work, but we haven't been in actual dialogue. So it's a great pleasure. And I'm a member of the Climate Psychology Alliance, the international one, but of course, much of its European activities are based in Great Britain. And then there's an active North American chapter. We'll probably talk a bit more about that today since you have been very active in that. But before going there, it would be very interesting to know something about your path towards being so engaged with climate matters and climate psychology. So would you like to start by sharing something about that journey?

Weston Sure. My journey, I come from a family of social and political activists and from Holocaust survivors to civil rights activists and towards the end of my father's life he was very, very involved in the human rights basis of climate change and was very sort of one of the early thinkers around how to use international legal systems to protect the planet for future generations. But I was actually a Johnny-come-lately to climate because I had very absurd notions about what the environmentalist movement was. I think in part because I was reacting to my father. I didn't want to do what he was doing.

Doherty: Mm-hmm.

Weston: But also I had this kind of archaic split in my mind between the environment and human issues. And I somehow took a kind of, there was a hubris in my idea that somehow I was gonna focus on poverty, I was gonna focus on racism, I was gonna focus on the hard issues. And environmentalism was just those people who cared about owls. And I was very dismissive, to be completely honest. And it wasn't until, well, I guess with the recognition of climate change, it became something clearly very different to me. I am very deeply committed and connected to my own environment, have been for a long time, but it was really around climate change that I began to think there's something more to this. And I've clearly missed the boat on a huge number of very, very important issues ranging from environmental justice and everything else. But that was not even enough to get me moving because then I went straight from awareness to denial. I was raising two very young kids and my father would give me book after book after book about climate crisis and every single gift-giving occasion he would give me these books and I would put them at the bottom of my bookshelf. I could tolerate understanding and looking at literally every other issue but I could not tolerate this one. I would turn the open the page and my anxiety level will rise and I would say not today.

Doherty: Hmm.

Weston: Part of what led me ultimately to this work is that I think that if I went through such a process of denial and pushing away and avoidance, surely I could understand where other people were coming from about why they felt the need to push it away. And I felt like I had a way of understanding that and having empathy for that and wanting to connect to the love of life that is often part of that denial, actually dysfunctional refusal to see, you know? And I really wanted to connect and I did not want to be in judgment towards people who were feeling those things because I knew for myself it was not because I was stupid, it was not because I was politically to the far right, it was because I cared too much about my children and my life that I was scared to see it. And I found that to be immensely eye opening and it gave me a foothold into the work that I could feel connected to and not run away from. So that was really my own origin and since then from that basis I have felt like I could stay with the problem and not flinch and that's been really important to me.

Pihkala: Thanks for sharing all that and really appreciating the honesty about those reactions even though they are not the ethical ideal but I really think that we need to be honest about that and I also believe as you said that it can give lots of understanding about where people are and trying to avoid binary interpretations between good and bad folks for example.

A couple of the emotional dimensions are course fear or threat related emotions which you are voicing and then also potential guilt dynamics and that may be also very difficult if one doesn't find a way to connect with these issues. I know that you have found so that probably helps with that also.

Can you share something about the work that you have been doing in practice? As a therapist, has it been so, as you supposed, that this history has helped you to understand the variety of people's responses?

Weston: Absolutely. Absolutely. I mean, I think one of the things I love most about being a clinician is that something happens when you go into the room theoretically or like the literal room or the metaphoric room where judgments really do go out the window and trying to stay very near to an experience that somebody has. And I find it incredibly powerful to relate to the experiences that people share. Why they are afraid, why they feel hesitant, why they have ambivalence, why they feel helpless, why they feel entitled. All of the different feelings that people have that can interrupt climate action or even climate awareness. I find it quite natural in many respects to have empathy for those starting points. Its interesting because I have tremendous political judgment, I have tremendous political sort of opinions and very strong moral and ethical codes that I think about in a larger political world. But there is something incredibly special about the therapeutic space that enables one to find a sense of empathy to the feelings that we might not feel otherwise find approachable.

That to me is incredibly important, again, to bring people closer and to recognize the humanity that is often part of the story that gets missed about why people turn away, disavow all the other things. So yes, I find my own experience to be immensely helpful. I find also being a clinician in general being immensely helpful to understanding how to communicate about this issue to the larger world, absolutely.

Doherty: That's lovely. That's lovely. You speak to something that's really important to me to that idea, the importance of the therapeutic space. And I think you've done a good job articulating this, this kind of holding two different realities. There's that political reality, like you say, where there has to be action and, and we have to commit to fighting battles against oppression and various things in the real world. But also, it's hard to put into words, but basically being able to have this, this space outside of the battlefield. What the metaphor I use is like the athlete, like they come off the playing field and they go to the sidelines or they go into the locker room. And during that time, they're not on the field. They're able to be real and to think and to share their feelings and so that's to me that's like the that's the therapy space it is special and then philosophically there's that old Rumi poem about “ there's a place beyond good and bad you know I'll meet you there” you know so it's philosophically a place we could we can examine our assumptions and on all that sort of stuff.

Its really helpful for people because some people haven't experienced that. They're always in the game 24-7. And they can't imagine stepping out of the game. So I think that's one of reasons why people don't want to get in the game. Does that make sense? They don't actually want to take it on because I feel like if they do, it'll be a never-ending cycle.

What were some of the books you remember some of the books your father gave you or what time frame in years are we talking about here when you were when you were still in your cocoon there?

Weston: The fifth extinction was one of them. Something by Gus Speth.

Doherty: They Knew by Gus Speth

Weston: certainly stuff by Bill McKibbin. I'm not remembering all of them now. My dad died in 2014. And I didn't really come to sort of full awareness of my own capacity to take this on until 2016. I don't think it's surprising that it wasn't until after he died. I felt very much an open space finally to sort of embrace it, to take it on, to see the magnitude of it.

I also think it's important to sort of name, which I have in other places as well, what the space was that enabled me to do that, which speaks to the collective nature of this, is that I was living in Missoula, Montana at the time, a friend of mine who had been very involved in climate work prior to this, he was part of holding something called the Climate Smart Communities, which is something that happens all over the country. And the particular one that she helped put together included experts, lay experts as well as professionalized experts in the entire, an unbelievable array of fields ranging from people who understood roofing to people who understood seeds, people who understood paint and climate, the tourism industry, the Native American sort of indigenous food sovereignty movement, like issues of homelessness.

Which they brought into the room such an extraordinary wealth of human resources and knowledge and capacity that was both professional and lay, that was both earned expertise and intellectualized expertise in the room, all gathering to talk about how are we going to adapt to climate change. And it was, think, the first time, think, where the Sunrise Movement had just sort of occupied I can't remember whose office it was, but the Sunrise Movement had just occupied somebody's office. And so there was this real energy around sunrise and then in the space of, I would say 150 people all talking about how we can preserve the world we love. And it was in that space that I finally opened up, I can do this, I can do this, I can step in, I'm not alone. People are bringing all sorts of histories and expertise to this, I can bring mine and mine is a mine is a psychological, mine is an attachment, mine of the understanding of trauma, the need of parenting. Like I all of sudden realized I had something to offer and it didn't need to be everything. And that I could join the multitude of people. And that gave such a space and permission to be part of, but not the only source. And that was just huge, a huge opening for me. And that was the time when my father had been giving me the books. I finally took them out and finally could get past the first or second page and say okay I'm stepping in stepping in and I'm ready and and I feel support support of a larger community of people.

Pihkala: Yeah, thanks for sharing that and it sounds like there was container big enough and also enough safety and one might name co-regulation of course here and some previous episodes of this podcast feature discussions about these dynamics. I'm thinking of the one with Rosemary Rorandel and one with René Lerchman for example and some discussions with Caroline Hickman also and the dynamic which was very eye-opening for me around 2015 that's if a person is scared it doesn't help to increase threat levels, it just works the opposite. But this also reminds me of a task I had just one and a half weeks ago, which was being the opponent of a dissertation defense, where the dissertation was about using trauma-informed methods in high school education on environmental themes, especially in relation to texts and language. So that was a quite interesting. Greetings to Päivi Koponen who was the dissertation defendant and there was lots of discussion about trauma dynamics and co-regulation and the need for safety also in relation to school spaces. Since I know that you have been much involved with these topics and you named attachment and trauma, so would you like to tell the listeners a bit about how do you see the connections between trauma and attachment to these dynamics we are talking about?

Weston: Yes, well, that's quite an opportunity. I believe so deeply in the social basis of being human and in the early, early, early formation and co-regulation that Winnicott said, there's no such thing as a baby and there's no such thing as a mother, there's a unit. We are always in dyad, if not triad and community, right? Like how far do we extend that out? And I think that the process of being able to hold intense feeling and recognizing one's ability to think oneself through it and feel oneself through it is utterly dependent on a relational space. And so the relationship of attachment is profoundly related to our individual collective capacity to honor and know and experience a feeling and make meaning out of that feeling, make meaning and then therefore take action on the basis of it. If we aren't in a co-regulated space, if we're not in a relationship where that is a safe thing to do, we're going to shut those parts of ourselves down, right? And they will be inaccessible to us as sources of information, as sources of validation about what we might need or want or do for the world in a traumatized system.

I did a lot of sort of family trauma assessments, in a traumatized system, the parent is going to check out, will not be available for a child, and therefore the whole system gets dysregulated. And you think about how do they then approach feelings of threat? How do they approach feelings of insecurity? How do they approach feelings of scarcity? All of those other kinds of things. There's not going to be a flexibility, a pliability, an emotional trust that if one names what you need, you will get it. And all of those things are vital for a resilient world that we're trying to create in this moment. So I deeply believe in attachment as a primary basis for healing and understanding trauma-informed care to your point, a scared person is not going to respond in a way that feels productive or collective out of fear. That's not going to happen. They will shut down. They will protect. They will defend. They will do all the things that people do. So I mean, there's a lot to say about that. I fear I'm not being particularly articulate about it right now. But to me its indispensable. And I've been working quite a bit with climate journalists and trying to understand what it's like to be a journalist reporting about this work while they're living in the communities where it happens. The level of trauma in the climate journalism field, how do they then write from that experience? How do they honor that experience? How do they write to an audience that's traumatized by the news, by the images? How do we not encourage avoidance? All of those kinds of things. Again, trauma-informed writing, trauma-informed care, trauma-informed education, how do we keep people regulated enough to stay present?

Which I think is what ultimately happened in that large collective space I had, right? That large collective space helped me regulate my own panic, which softened me into being able to actually take in the information, not defend against it, not push it away. That to me is the heart of why we do collective work, why we need to think of it at a community level, is that we need to keep people safe enough internally to hear what's happening, and then to relate to each other as allies as opposed to threats.Very hard work, given the political system and the terrain that we're in at the moment.

Pihkala: Yeah, that's wonderful and before I give the floor to Thomas who probably has a lot on his mind, I'll just say that I think you are being very clear and articulate about quite complex dynamics. So well done.

Doherty: Yeah. I agree. I was I was going to say the same thing. It is you. You kind of gave a very concise, definition of attach an attachment, trauma based approach to this work. So it does start with the family and it is a lot. Yeah, It's so great to have these conversations to get really into the nitty gritty of this kind of work because in the climate elephant I talk about, where there's all different parts of the elephant and we're blind and we get our part and we think this is what climate change is. And then we talk to someone else and they say, well, yes, but this is also what climate change is, and then we realize, okay, we have multiple truths going on. And that I think is one of the hardest things. That's why I really love your story about the climate smart communities, because the other entree into this is more of a positive psychology direction as well, which is not about trauma, but about, I can contribute. The fact that they call that a climate smart community, they didn't call climate traumatized community. So they're approaching it from a position of strength, positivity. And so many people gravitate to that. They would not go to a therapy group. That's not what they're interested in. Many of those climate smart people are not interested in therapy. They're interested in making a change. And so the idea of being smart is really a great framing and that provides a container as well. And then you can approach this as, oh I have a job, you're a roofer, you do HVAC systems, you do the community planning, but I'm a therapist and I have a job in the community. So that's so important.

Because therapists are just as important as firefighters and doctors and plumbers. And so you were able to say, wait a minute, I think, that's what Rosemary Randall, when she was doing her climate, that's what she realized too, was like, wait, I do have a role here already just right off the shelf. And so that's the other important piece about things like the Climate Psychology Alliance is that we have a lot of willing workers. So it's very much the same as climate and sustainability moving through other industries. It's moving through the therapy industry. And there's many highly, highly trained, highly gifted, highly gifted people who do know all this nuanced stuff about attachment and trauma and positive psychology and cognitive behavioral psychology, interpersonal and, you know all the different therapy flavors. And so you were able to say, wait a minute, I can help.

If we had another episode maybe you can unpack your complex relationship with your father because, know, we all have parents. We all have parents. You can have issues with authority and issues with authority, right? I mean, you have issues with authority in the larger sense, but you also had issues with authority, right? so, but we're all, we all family. yeah. What?

Weston: We sure do. My first political button, Thomas, was a question authority! My first political button was a huge one that said “question authority,” and that has remained.

Doherty: Yeah, and the psychoanalytic people out there always know that, you know, the parent and the family relationships are not very far behind us. But, you know, that's another story. But you don't even have to go into it just to name that there are those dynamics. That's helpful for people to know. My daughter will probably have a similar experience because, you know, she grew up in a household where climate change was talked about. luckily she is in Portland, so it's quite normative for everyone to be conscious. So she doesn't feel like she has to be the truth teller in the family, you know, but you know, everybody will have their family individuation process or whatever that, whatever that means.

How about we move to the present and Climate Psychology Alliance has got so many things going on and I know behind the scenes you just deserve like a really big award and a know a big bouquet of flowers for all the work that you've been doing. We know it's very difficult to run nonprofit groups and things like that so there's a lot there but what are you what are you proud of with the CPA right now and what what are some of the growing edges? in the organization that would be nice to shed some positive attention to, do you think?

Weston: That's a wonderful question and thank you. And I bet many people would have different answers to that same question. I think the thing I'm most proud about within CPA and what makes it somewhat different from other organizations and I just wrote about this in the newsletter in a kind of smaller way, is that it takes seriously that it's a membership-based organization. It's not a small staff that is determining a whole bunch of policy around grants. It really is membership-based and we have close to 750 members. I think its growth is entirely limited by capacity to hold who joins and finding kind of productive ways for people to feel connected and in community with each other. think that 750 by no means represents the volume of people in the mental health field who are wanting to take part and engage around issues of climate. And so I think it's just incredibly powerful to envision that there's even 750 clinicians in communities all around the United States who are trying precisely to think about how can I contribute my skills?

Of a community that needs lots and lots of skills, as you say from plumbing to seed work to farming to creating sort of alternative school systems around the summers, all of these other kinds of things. What can I contribute as a therapist in this idea of a mutual world, mutual creating of a world, to think that we are teaching people that it's okay to do that, that they can be part of a larger process, that they don't have to think of their clinical skills as being narrow and individualized, but they can be part of a larger collective process around the climate movement. That that is something that's happening all around the country, even in an embryonic state, to me is so inspiring and so beautiful and frankly different from all of the other, most of the other climate organizations. And that's with intention. What that also means is it's far messier. It's messier, it's harder. The kinds of questions that we are engaging in and how do we communicate effectively? How do we have a democratic process and still organize? How do we raise grants when we're this weird hybrid wonky thing? Are we membership? Are we mental health? Are we climate? What are we? It makes it very, very wonky, but it also makes it to me have a heart and a soul that I really value deeply.

I think some of the growth points, and I don't think there will be an answer to this, to something that Panu and I were talking about at the beginning is how do we situate ourselves in a political moment that is deeply, deeply fraught and where the issue of climate might not be front and center for many, many people. And that's not again because of denial. It's because the threats that we're facing as a community, as a population, as a country, as a planet are so interwoven, right? So when we think about threats to immigration, when we think about threats around authoritarianism and democracy. That's not unrelated to climate. Our ability to be active, our ability to name, our ability to collectively organize, all of those things are deeply implicated. But as a membership organization, we all have very, very different comfort levels with those questions. We are located geographically in very diverse places, politically diverse, suffering from climate change does not have a political label on it, although you might acknowledge some may have may not acknowledge it as climate. So how do we situate ourselves ethically and responsibly and clarity in this political moment? That's not an easy thing to figure out. And it is what keeps me up at night. It's what gives me tremendous excitement and tremendous fear. It makes me feel like I'm doing terrible work as well as very important work. It's very confusing. And I think that's a growth point for all of us. And we hold different pieces in the organization around that.

I think the other growth point is to move away from being kind of a virtual training organization to really empowering community members and clinicians on the ground to do the work in person. So we are trying to get, and this is where the philanthropy field really, really needs to step up. How do we actually fund the work on the ground so that we can go into agricultural communities and have some of these listening circles that are tailored to the geographically and politically specific spaces they're in. How do we reach STEM scientists who are feeling horribly demoralized after they've lost all their jobs and are seeing what's happening in the federal government? How do we provide support? How do we learn about mutual aid if we don't have money to actually fund clinicians to do this work when they're still working out their own livelihoods, right?

So we want to move away from being a training organization that thinks only about resilience and the importance of doing these things and actually having the capacity to do it all over the country. Because that's where really rubber hits the road, right? We're all committed to actually doing the work and feeling the work and not just talking about the work. And that needs real money because people can't do this on volunteer fumes over the long haul. And this has been profound, an organization of unbelievable volunteers.

Primarily volunteers still, which speaks to the dedication people are feeling. mean, people are giving unbelievable amounts of time that's not compensated. And you imagine what could happen if people felt like there was some breathing room to actually do the work on the ground and make the connections that need to be made.

So that's to me the biggest growth edge and that's a direct sort of commentary about sort of the climate and philanthropy world. Is there space for climate and mental health? How do we forge that space?

Myself, our organization is part of a coalition that's trying to develop that, is to really begin the process of educating the philanthropy world to this need. Because otherwise, it's only going to stay up here in the internet sphere and the webinar sphere. And that reaches such an exceedingly limited group of people that it's really not where we want to stay. So that's what I would say.

Doherty: Yeah, I'm glad you brought it to that level because that is, you have a job, but like, you as one of the directors, co-directors, you you're in the real nitty-gritty of one very specific part of the climate field, which is helping to run a large nonprofit organization. And there's many listeners that would know what that is like. Not all of us have to do that particular job, but that is itself a very special job. And also, I just want to say, yes, let's just give a shout out to all the volunteers that have helped with the CPA. I feel like it's a right of passage for a lot of therapists to have done a tour in the CPA world. And you do what you can. you know, lot of us, Panu and I have dealt with this over the years too. I know we don't know what we're capable of and we over commit and then we give what we can and then we realize we need to pull back and that's a natural part of this work.

So, but it's, there's a place to go for it, you know, that doesn't require you just to be a sole person. And for some people, they really need a group to get going. So, so congratulations to everyone in the CPA and that whole—I don't even know, there was not one person that started it. Obviously, it was this coalescence of coalescence of things. But Rebecca, you're holding the holding one of the, you know, the place, place of director, directorship today. So we're honoring you. Well, we could go further, as we always say, but we have to wrap up. But this has been a really nice little window into your world, Rebecca. I really, know you're so busy. I really appreciate you coming in today to talk with us.

Weston: Thank you.

Pihkala: Yeah, warm thanks also on my behalf. There would be many teams to continue and also honouring and being grateful for the integration of realism and a positive vision that you are showing. So all the best with that.

Weston: Thank you. Thank you for this opportunity.

Doherty: We are, we're going to stop in a second, but you are still alive.

Weston: Well, so then I will plug your book because I am in the middle of reading it and I am finding it to be, not all of it is particularly new, but the way you're framing things and the way you're talking about the need to hold all of the different feelings very much was top of mind today for me. And I look forward to writing something about it, but I've been really excited reading it and I want everyone on this podcast to check it out when it comes out. That it really does offer a way into these feelings, a way into being a whole person in these feelings. And especially bringing the parts of oneself that feels capable, that can feel joy, and how those need to be parts of our wellspring of action. Again, just really, really like the book so far, really value it, and want to, and I will be finishing it and getting something to you. So, high praise.

Doherty: Well, thank you that I didn't I didn't even ask for that nice little testimonial but I really appreciate that. Surviving climate anxiety is the book that I finished that's coming out on October 7th. So thank you so much for that.

We're going to wrap it up, Panu. I know you've got another meeting to go to and you're doing your research work. So thank you all very much and listeners and everyone, take care.

Weston: Thanks. Bye bye.

[music: “CC&H theme music”]

The Climate Change and Happiness Podcast is a self-funded volunteer effort. Please support us so we can keep bringing you messages of coping and thriving. See the donate page at climatechangeandhappiness.com.